What Makes a Successful Game Based Learning Environment

Few blended learning studies exist to date, but those that do highlight some best practices. Legends of Learning’s own GBL study, “Substantial Integration of Typical Educational Games into Extended Curriculum,” identifies several elements essential to overcoming challenges found in blended learning environments. They include the following three:

1. Student choice from a set of teacher-curated games

2. Competency-based game mechanics

3. Strong teacher instruction

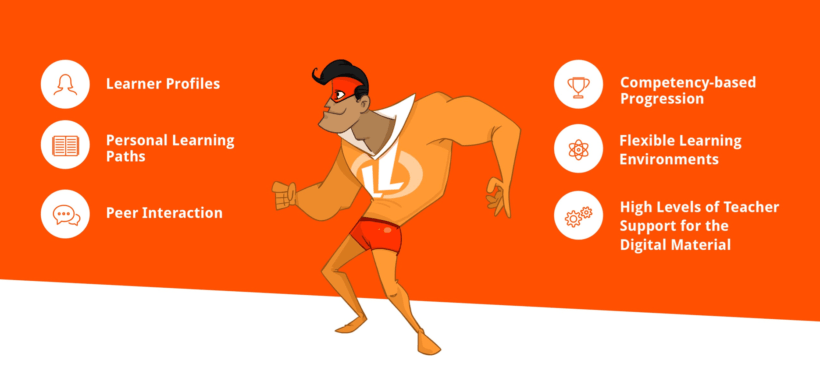

A Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation RAND study, Interim Research on Personalized Learning, notes an additional four attributes common to successful blended learning environments. Jamee Kim and Wongyu Lee name two more characteristics in their study conducted at Korea University. The six cumulative characteristics are:

1. Learner profiles

2. Personal learning paths

3. Peer interaction

4. Competency-based progression

5. Flexible learning environments

6. High levels of teacher support for the digital material

The qualities further detail the three identified by Legends of Learning and Vanderbilt University in their collaborative study. The six also recall James Paul Gee’s 16 tenets, suggesting they build upon the best practices of the past while encountering the present and looking forward to the future.

Turning Curriculum into Interactive Game Content

However, true success with GBL cannot be limited to engagement alone. Games must help educators deliver lessons for them to have long-term value and impact. That means they must connect to the curriculum in some way, as well as support other learning goals related to the subject matter, lesson plan, or grade level.

Robert J. Marzano, who conducted a five-year study of game based learning, makes the argument in his findings. He says, “If games do not focus on important academic content, they will have little or no effect on student achievement and waste valuable classroom time.”

European researchers Venera-Mihaela Cojocariua and Ioana Boghiana also believe that games need to have a clear and understood role in the classroom. They state, “In order to exploit the advantages of using game-based learning in class, there is a clear need for standardization and regulation on the use of games in teaching-learning-evaluating.”

Legends of Learning and Vanderbilt University similarly tie GBL success to the rigors of learning. Their study shows that GBL efforts integrated with the classroom curriculum cause quantitative and qualitative improvements in content mastery as well as engagement.

Balancing engagement with content mastery remains a challenge. If students aren’t interested in the teacher-approved games, they won’t play them. Gee and other researchers note that games must be interesting and fun, while delivering educational content, for them to produce results.

In a productive GBL environment, learning and engagement operate hand-in-hand. One cannot succeed without the other.

As a result, educators will need to carefully evaluate games to make sure they both engage students and support the curriculum.